Author: Junichi Kanzaka

Abstract:

This study examines the functionality of the manorial system in thirteenth-century England, characterizing it as an institution grounded in self-enforcing agreements between lords and peasants. Drawing on data from the Hundred Rolls of 1279–1280 and employing quantitative analysis using Instrumental Variable Two-Stage Least Squares and Instrumental Variable Tobit, we find no significant correlation between rental rates per acre of customary tenements and the degree of manorialization. These findings suggest that the level of customary rents was not imposed through“extra-economic coercion”by lords but was instead the result of negotiated agreements between lords and customary landholders. On the one hand, lords enhanced their bargaining position by monopolizing larger portions of land within a vill. They also benefited from the contributions of substantial customary tenants, particularly through labor services and cooperative agricultural practices. Consequently, lords had incentives to extract a greater share of rent in the form of labor services. On the other hand, the active participation of customary tenants in the manorial economy strengthened their bargaining power, resulting in rents that generally remained below market-determined levels. Labor services, in particular, could be advantageous for tenants during periods of demographic pressure when labor was abundant. However, certain freeholders were excluded from the community norms in which lords and customary tenants engaged in reciprocal arrangements. Thus, the inequities of the manorial system stemmed less from exploitative rents or coercive labor demands, and more from its structurally exclusionary nature.

Published on Cliometrica (2025)

Open access and free to download:

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-025-00315-9

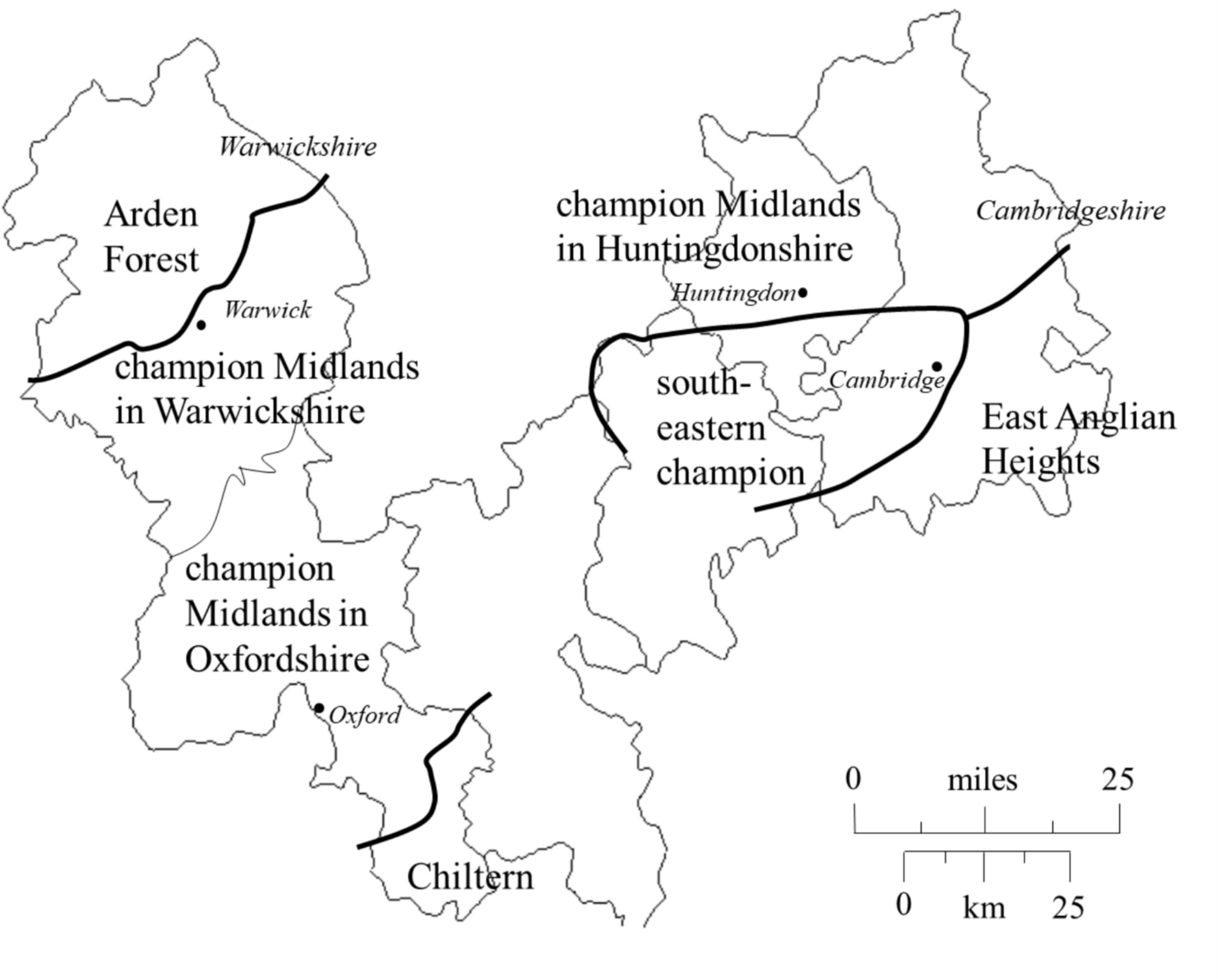

Landscape regions within the areas covered by the hundred rolls